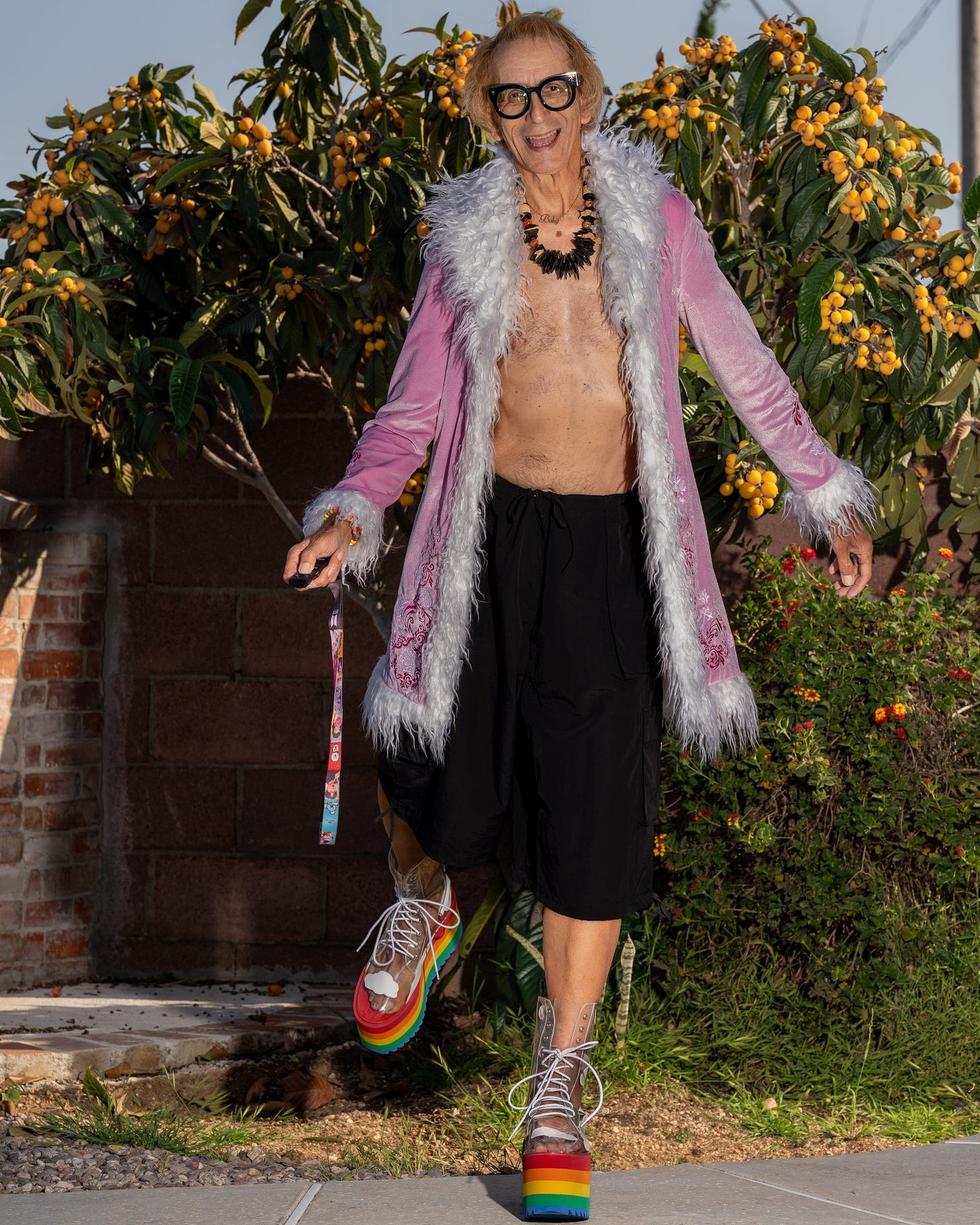

Pink is a Power Color for Boys

The Pope wears Dolce & Gabbana, why can't you?

The strict girl:pink, boy:blue divide only dates from the mid-20th century. Just a few, scant generations ago the situation was completely different. In an article on baby clothes in the New York Times in 1893, the rule stated was that you should “always give pink to a boy and blue to a girl.” Neither the author, nor the woman in the shop who she was interviewing were quite sure why, but the author hazarded a tongue-in-cheek guess, “the boy’s outlook is so much more rosy than the girl’s,” she wrote, “that it is enough to make a girl baby blue to think of living a woman’s life in the world.”

— Kassia St. Clair, The Secret Lives of Colour, 2017

In 1918, a trade publication affirmed that this was the “generally accepted rule” because pink was the more decided and stronger color, while blue was more delicate and dainty… Pink is, after all, just faded red, which in the era of scarlet-jacketed soldiers and red-robed cardinals was the most masculine color, while blue was the signature hue of The Virgin Mary.

— Kassia St. Clair, The Secret Lives of Colour, 2017

Not every boy who puts on a dress is communicating a wish to be a girl. Too often gender dysphoria is conflated with the simple possibility that kids, when not steered toward one toy or color, will just like what they like, traditional gender expectations notwithstanding. There is little space given to experimentation and exploration before a child’s community seeks to categorize them. Boyhood, as it is popularly imagined, is so narrow and confining that to press against its boundaries is to end up in a different identity altogether.

— Sarah Rich, Today’s Masculinity Is Stifling, The Atlantic, 2018

“Boys can like beautiful things, too!”

But they can’t. Not without someone looking askance. To embrace anything feminine, if you’re not biologically female, causes discomfort and confusion, because throughout most of history and in most parts of the world, being a woman has been a disadvantage. Why would a boy, born into all the power of maleness, reach outside his privileged domain? It doesn’t compute.

— Sarah Rich, Today’s Masculinity Is Stifling, The Atlantic, 2018

When the Boys Scouts of America announced that they would begin admitting girls into their dens, young women saw a wall come down around a territory that was now theirs to occupy. Parents across the country had argued that girls should have equal access to the activities and pursuits of boys’ scouting, saying that Girl Scouts is not a good fit for girls who are “more rough and tumble.” But the converse proposition was essentially nonexistent: Not a single article that I could find mentioned the idea that boys might not find Boy Scouts to be a good fit—or, even more unspeakable, that they would want to join the Girl Scouts.

If it’s difficult to imagine a boy aspiring to the Girl Scouts’ merit badges (oriented far more than the boys’ toward friendship, caretaking, and community), what does that say about how American culture regards these traditionally feminine arenas? And what does it say to boys who think joining the Girl Scouts sounds fun? Even preschool-age boys know they’d be teased or shamed for disclosing such a dream.

— Sarah Rich, Today’s Masculinity Is Stifling, The Atlantic, 2018

An ordinary painting, as we understand it in its general matter, is for me like a prison window, whose lines, contours, shapes and composition are determined by the bars. For me, the lines materialize our state of mortals, our affective life, our reasoning, even our spirituality. They are our psychological limits, our historical past, our education, our skeleton; they are our weaknesses and our desires, our faculties and our artifices.

Across the roughly eight hours of content we watched together—all of it Nickelodeon programs aimed at kids 2 and older—68 percent of the toy commercials foregrounded either only girls or only boys playing with the product. The all-girl commercials tended to use pastel colors, or pinks and purples; they mostly advertised dolls and plush toys, and products related to beauty and fashion. The all-boy commercials, in contrast, drew on colors such as yellow, green, red, and blue. Many of them promoted toys based on characters from video games—a Mario action figure, for instance, was tasked with rescuing Princess Peach—or toys related to transportation or adventure.

— Stéphanie Thomson, Why Are Toy Commercials Still Like This? The Atlantic, 2023

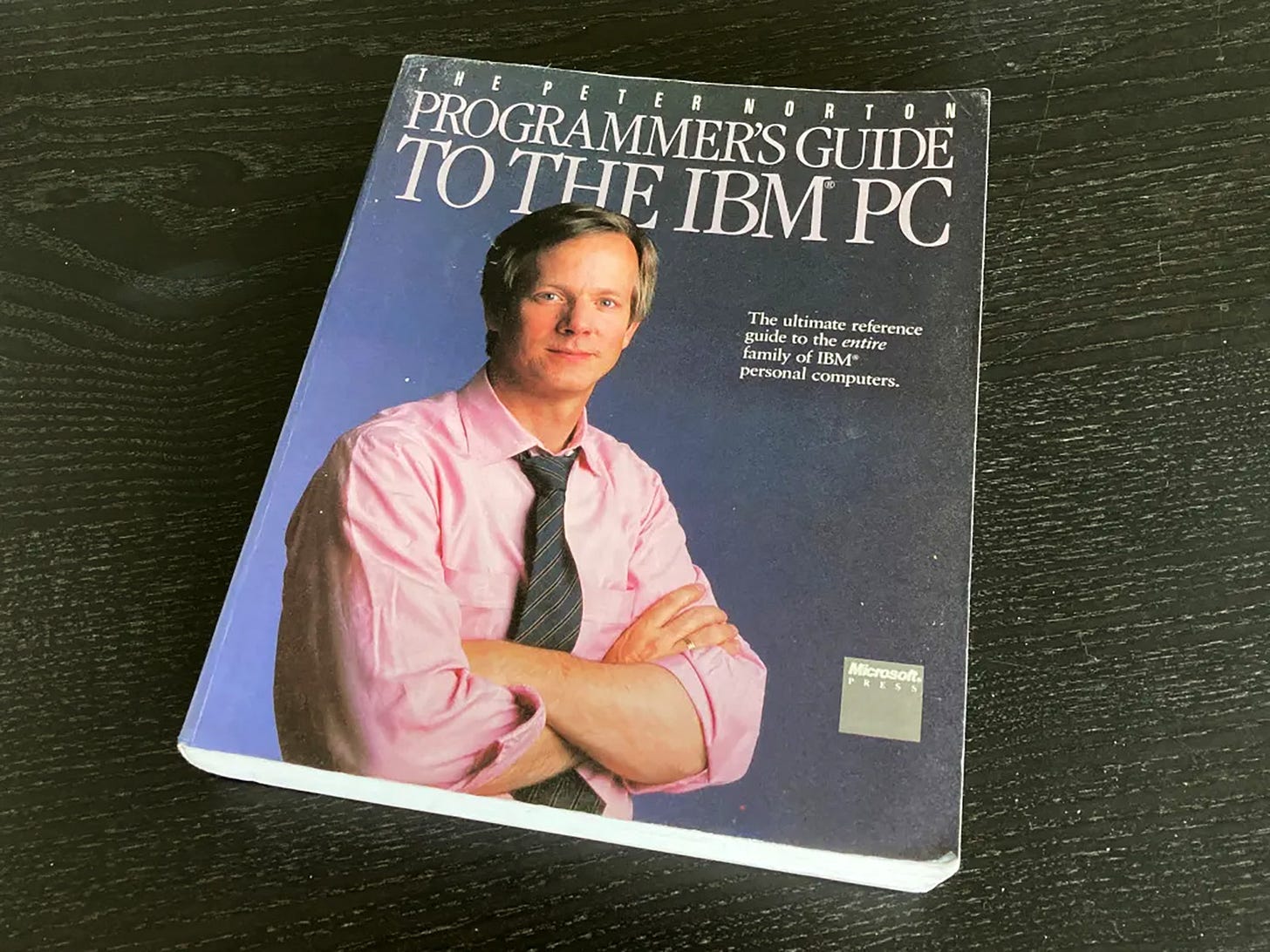

Peter Norton / De Programmatica Ipsum

Where have you gone, Peter Norton? / Technologizer

In a 1991 episode of The Simpsons, Homer shows up to work dressed in pink after Bart tosses a red hat into the laundry; his boss assumes he’s gone crazy and later gets him committed to a mental institution.

— Lenika Cruz, Will a Major Sports Team Ever Wear Pink?, The Atlantic, 2014